Following on from last week’s ‘What is an entrepreneur?‘ post, I thought we’d look at how to act like a startup.

If you remember, a team had asked me to help them think differently. They were stuck in a rut (building something that they weren’t sure was going to solve the most important problem) and wanted a different approach. They had asked me to help them start thinking like a startup.

I only had 24 hours to think about how I’d structure the 60-minute session, so had to really get to the crux of the matter quickly. This is what I went with.

What is a startup?

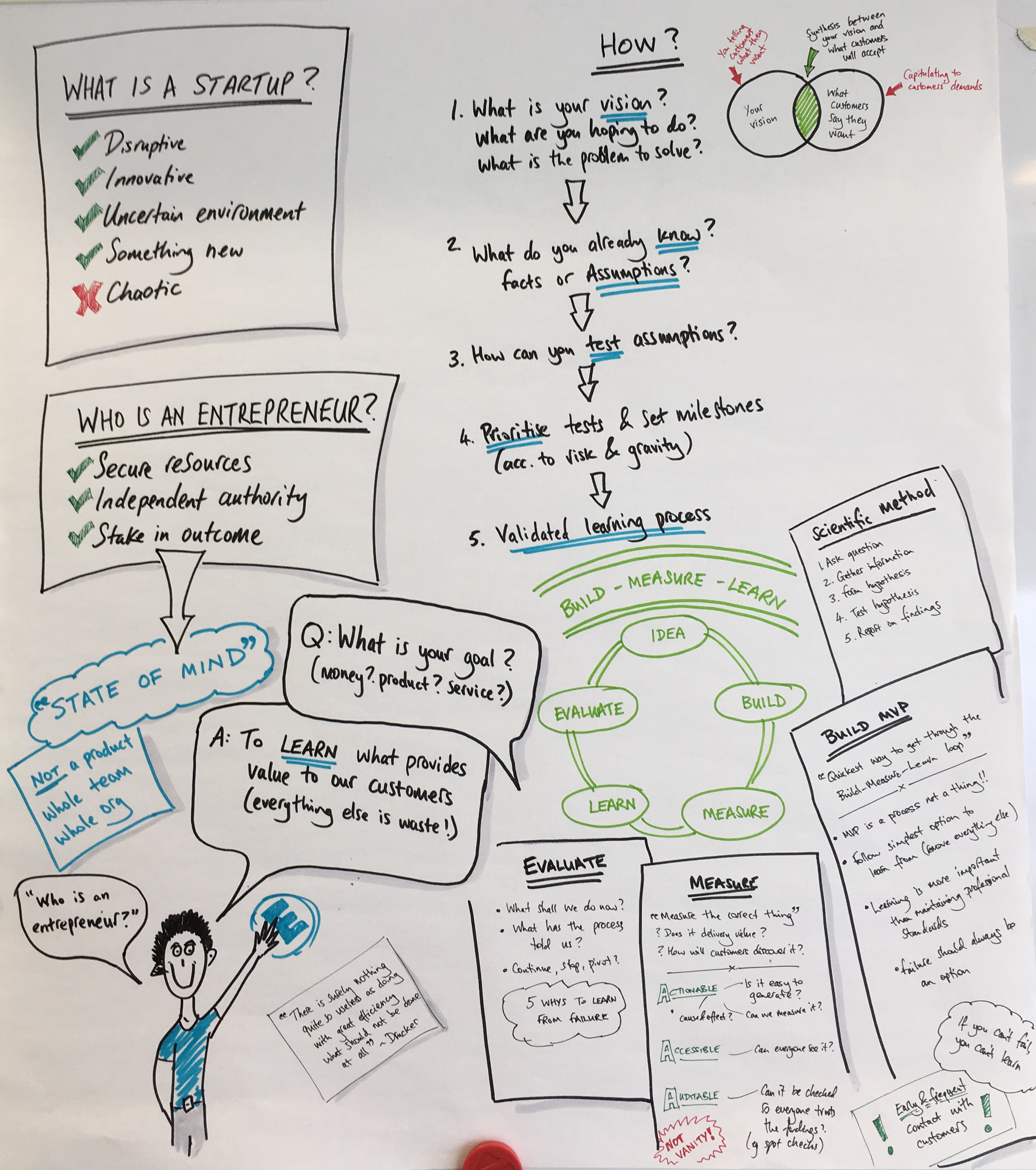

When I ask for words that differentiate a startup from other approaches, what do you think of? People shout out words like cutting edge, original, unique. unknown, altered-state, ground-breaking, original, vanguard, inventive, visionary, risky, unclear. We summarised it as new and innovative; disruptive and in an uncertain environment. But I parked “risky” and “chaotic” to come back to.

What is an entrepreneur?

You are one. It’s a mindset. See last week’s post for more on this.

What’s the goal?

“There is surely nothing quite so useless as doing with great efficiency what should not be done at all” ~ Peter Drucker

Regardless of what your specific field of interest is, our goals are all aligned: trying to learn what provides value to our customers. This is what the team said they were excited about. They wanted to get clarity on what was most needed by their users. But how could they do this?

How do you do this?

We had a discussion about what they thought their goal was? What is their vision? I pointed out that, in Lean Startup, Eric Ries’ talks about how you are not delivering your vision to customers (because that would be telling customers what they want), but nor are you just giving users what they want (that’s capitulating to their demands); you are focusing on the synthesis between your vision and what customers will accept. This area often generates some discussion, especially if your providing a service in the public sector. But step 1 is deciding your vision: what you’re hoping to do and the problem you’re trying to solve.

Once you’ve settled that, the team can then think about what they already know about it. Write everything down and separate them into two columns: what is a fact and what is an assumption. This is where it gets interesting because nearly everything the team says starts in the fact column but moves over to the assumption column. Step 2: establish what you know: fact or assumption?

Next comes some brainstorming on how you can test the assumptions. This can be tricky for teams stuck in a build-focused mindset. Surely building the thing is the best way to test our assumptions. Not really; it’s undoubtedly an expensive way though. Step 3: work out how to test your assumptions.

It’s now time to decide which assumptions you need to validate first. What would be the most important assumption to turn into a fact? What would make the most difference to your team trying to fulfil the user need from step 1? Step 4: prioritise the assumptions you are going to test. You can set some milestones here too – it sometimes helps teams to keep their focus and inserts some motivation. I think you can swap steps 3 and 4 around if you want – there are pros and cons for each way.

Finally, step 5: test the assumption using the build-measure-learn process that Lean Startup is best known for. In the session I explain the scientific method (more about that in future posts). I stress a few points here: it is important that the test has the capacity to fail: that is, the assumption that you are testing can be proven correct or incorrect. If you can only prove it is correct, then there’s no value in testing it. Also, make sure that your measure step is not about making the team feel clever.

It’s only a brief overview of a different approach but it stirred enough interest for them to get started and start trying new ideas.

So is a startup new and innovative? Yes. Disruptive and beneficial in uncertain environments? Yes. Risky? Well, there’s always some risk involved, but our approach can significantly magnify or minimise it. And chaotic? Not if we work in this way.