There are three pillars underpinning any empirical process: transparency, inspection and adaptation. Teams are generally familiar with inspection and adaptation, after all, frameworks like Scrum are quite prescriptive about the need for retrospectives. Teams often overlook transparency.

There are a number of ways in which a team can be transparent. Firstly, they can be transparent in the way they work: bring stakeholders closer, work with them everyday, allow feedback to flow in both directions and share the risk of taking a certain direction. Secondly, they can make progress visible: burn down charts and a whiteboard are the traditional methods for showing progress against sprint goals. A simple report to show progress at all levels of planning, from sprint all the way up to vision, can be incredibly effective at reducing the number of ‘when will it be done?’ conversations. Finally, information needs to travel in both directions. Stakeholders and those in product roles, especially those who work directly with a team, must be transparent too. Product direction in the form of roadmaps, release plans or something similar can be made visible to the team so that they are aware of the overarching goals they are contributing to delivering on.

Without transparency we don’t get feedback, and if we don’t have feedback we are far less likely to deliver the right thing. In the worst case scenario, requirements become specifications, and all of a sudden our empirical process is masquerading as something much more deterministic. The principles behind the Agile Manifesto are clear: “Business people and developers must work together daily throughout the project”. Focussing on this principle creates transparency and ensures everyone gets the feedback they need for them to be collectively successful.

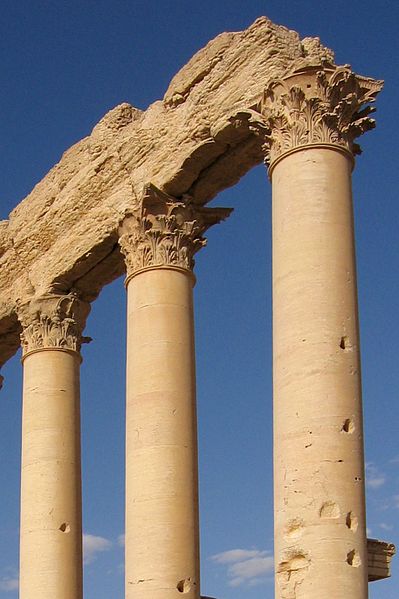

If one of the 3 pillars is missing, or if they start to crumble, relationships, processes and your organisation’s ability to deliver on its goals becomes unstable.

Image credit (under creative commons licence): Wikimedia Commons

I agree with you Jim: it sometimes feels like you’re having to drag information out of ‘the business’ and that information sometimes just appears from nowhere (when it must have been known for a while).